Armenia and Bjni: How history happened here.

Bjni is a valley village located in the Kotayk province of Armenia, nestled between overlapping mountains and the Hrazdan River. It is about 40 minutes northeast of Yerevan on the road to Lake Sevan.

Settlements in Bjni. (Image courtesy of Armenia-Tour.com)

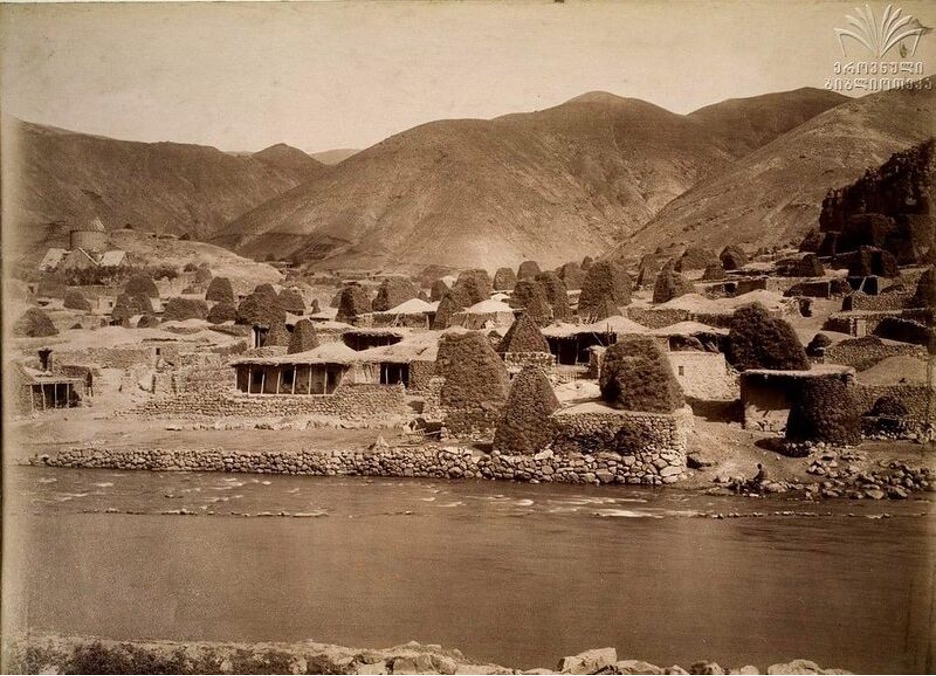

Bjni in 1885. (Image courtesy of Armeniapedia)

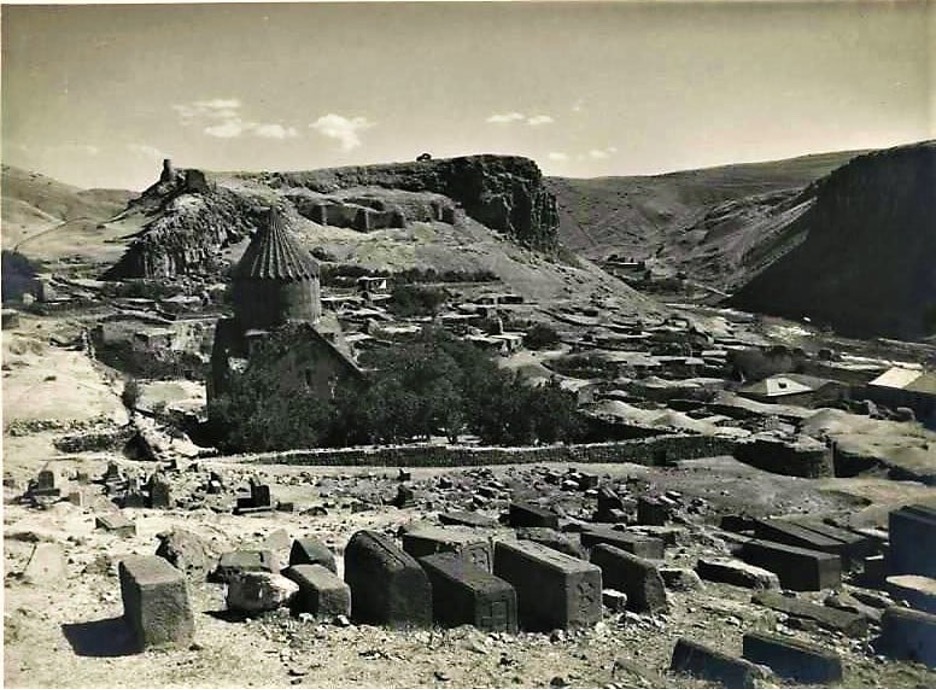

Bjni in 1955. (Image courtesy of Sergey Shimansky and Armeniapedia)

Bjni in 2012. (Image courtesy of Vigen Hakhverdyan)

Bjni is one of the prominent centers of education and culture of ancient and medieval Armenia. It is the birthplace of the 11th-century prince, linguist and scholar Krikor Magistros. (The word “magistros” is Latin for master. It was a title used in the Middle Ages by the Roman and Byzantine Empires, given to a senior person in authority, or to one having a license from a university to teach philosophy and the liberal arts.) Krikor studied both ecclesiastical and secular literature in Armenian, Syriac and Greek.

He collected Armenian manuscripts of scientific and philosophical value, including the works of polymath and philosopher Anania Shiragatsi, and translations from Andronicus, Olympiodorus and Callimachus. Krikor Magistros translated several works of Plato—The Laws, the Eulogy of Socrates, Euthyphro, Timaeus and Phaedo. He was one of the first poets to adopt the use of rhyme introduced to Armenia by the Arabs.

The first recorded mention of Bjni was by the 5th-to-6th century chronicler and historian Ghazar Parpetsi.

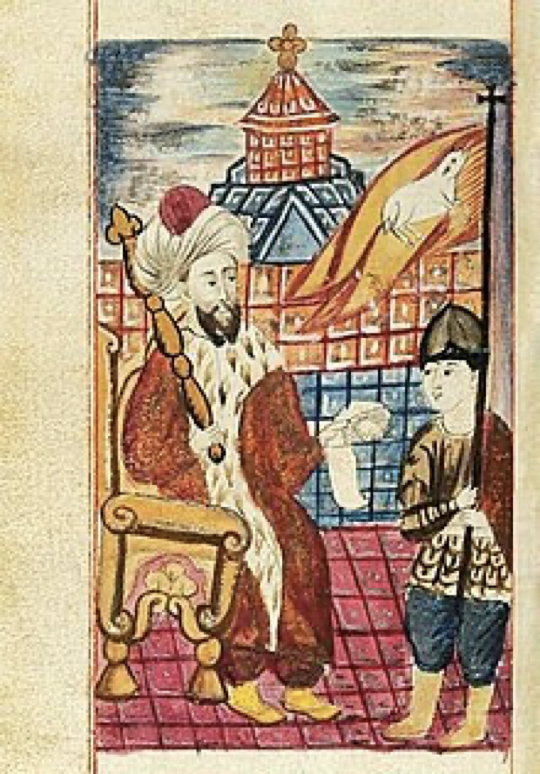

A portrait of Krikor Magistros from an 18th century manuscript.(Image courtesy of Encyclopedia.am)

Monument to Ghazar Parpetsi in Parpi, a village near Ashtarak, Armenia. (Image courtesy of LukGasz.)

Parpetsi is best known for writing the History of Armenia, which is composed of three parts. The first part is about Armenian history from the mid-fourth century and life in Armenia under Sasanian rule until the deaths of Armenian alphabet champions Sahag Bartev and Mesrob Mashdots in the mid-fifth century.

Saints Sahag Bartev and Mesrob Mashdots championed the Armenian Alphabet, invented by Mashdots in 406 A.D. and were responsible for spreading spiritual and intellectual enlightenment throughout Armenia. (Image courtesy of HOLY TRANSLATORS | SAHAG & MESROB (stjohnarmenianchurch.org)

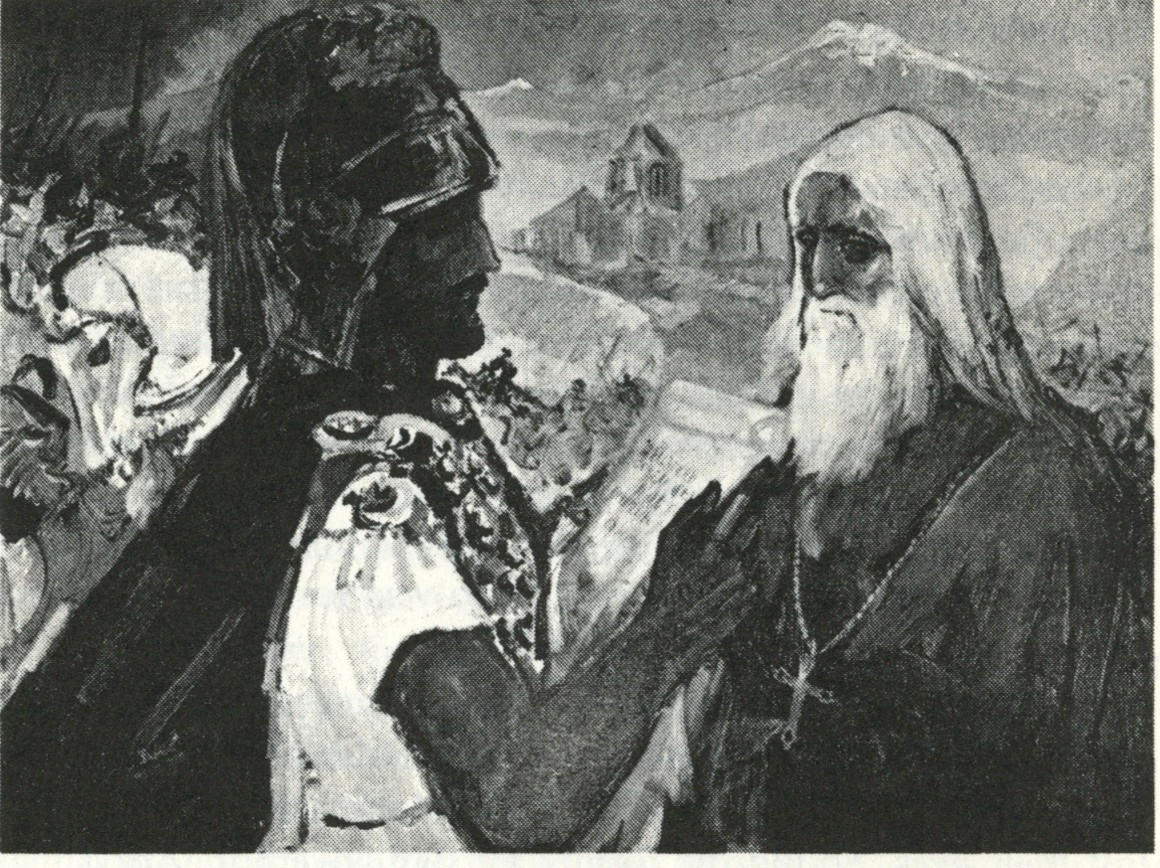

General Vartan Mamigonian (center) and leading cleric Ghevond Yeretz (left) are a patron saints of Armenia, credited with preserving the Christian Armenian identity. (Image courtesy of ArmeniaDiscovery.com. Vardan Mamikonyan (armeniadiscovery.com)

The second part of Parpetsi’s History concerns the events leading up to the battle of Avarayr in which the Christian Armenians under the leadership of General Vartan Mamigonian resisted a Persian drive to convert the Armenian nation to Zoroastrianism, a fire-worshipping religion.

The third part of Parpetsi’s History follows up on the Vartanank wars and the 484 A.D. signing of the Treaty of Nvarsag with Persia granting all Armenians human and religious rights.

In that year, after a half century’s struggle with their Persian overlords, the Armenians won certain religious and political liberties through a document which has come to be called the Armenian Magna Carta – The Treaty of Nvarsag. (Image courtesy of Paul Guiragossian. (The Treaty of Nvarsag – Armenian Prelacy)

In the 11th century, the lands of Bjni were passed to the Pahlavouni royal family. During this time, the Pahlavounis built and commanded various fortresses throughout Armenia such as Amberd and Bjni. The house of Pahlavouni played a significant role in all the affairs of the country.

The inscription surrounding the central cross on this small khachkar mentions “Basil the servant of God,” who may be the Cilician Armenian Catholicos and military figure Parsegh (Basil) Pahlavouni. The first three catholicoses, heads of the Armenian Church at Hromkla [from the Roman for “castle,” based in Aintab in present-day Turkey] were also from the Pahlavouni family. Basil Pahlavouni fought with the Crusaders against invading Muslims. (Image and caption courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where this khatchkar currently resides on loan.)

Bjni also played a significant role in Armenian life during the Pakradouni dynasty, whose royal family members incorporated the estates of Bjni and other principalities into their kingdom.

The Pakradouni family first emerged as nakharars (members of the hereditary nobility of Armenia) in the early 4th century. The first Pakradouni prince identified by historian Cyril Toumanoff, Smpad I, lived at the time of the Armenian conversion to Christianity (301-314 A.D.). Originating as vassals of the Kingdom of Armenia of antiquity, the Pakradounis rose to become the most prominent Armenian noble family during the period of Arab rule in Armenia, eventually establishing their own independent kingdom. Their domain included regions of the Kingdom of Armenia such as Shirag, Pakrevant, Kogovid, Syunik, Lori, Vasbouragan, Vanand, Daron, and Dayg. (Image and text courtesy of The Armenian Diaspora Foundation.)

At the beginning of the 13th century, the lands were passed on to the Zakarian Family, a branch of the Pahlavouni royal family.

Zakarian royal coat of arms with the iconography of a lion and a bull, at Keghart monastery in Armenia. (Image courtesy of Beko.)

A century later in the years 1386-1388 the Turco-Mongol conqueror Tamerlane (or Timur Leng) invaded and destroyed the village of Bjni.

The remains of the 9th-to-10th-century Bjni Fortress of the Pahlavouni family sit along the top and sides of a mesa that divides the village almost in half.

Chroniclers named the Fortress of Bjni the “unapproachable abode of gods”. The village of Bjni was mentioned in The History of Armenia by Armenian historian and chronicler Ghazar Parpetsi in 5th century, while the Fortress itself has been spoken of since 10th century, when it began to gain political significance. In the 11th century, the ruler of the town, Vasag Pahlavouni, renovated it and surrounded it with walls. After that, the city-fortress under his command was able to withstand assaults of nomadic tribes. The complete impregnability of the Bjni Fortress isn’t so surprising as the hilly environment alone made it quite difficult to even reach its outskirts. Imagine how much training enemy soldiers would have needed to undergo to be able to run up the hill and still have the ability to fight. (Image and caption courtesy of Art-A-Tsolum.)

The larger portion of the village is located west of the mesa and curves south, while a smaller portion is east. Wikipedia states that the walls of the Fortress “may only be seen from the western side of the village, and are easiest reached via a dirt road that forks and goes up the side of the hill.” The Fortress itself is 1,504 meters (4,934 feet) above sea level.

The main mesa of Bjni is a broad, flat-topped elevation with one or more clifflike sides. (Image courtesy of Art-A-Tsolum).

Most of the Fortress walls, working secret passages, as well as the ruins of many structures of various purposes have been preserved. (Text and images courtesy of Armenia Planet).

At the top of the Bjni mesa, there are some sections of walls still preserved, traces of where foundations had once been, the stone foundation of a church from the 5th century, a medieval structure that still stands (currently being rebuilt), two cisterns one with vaulting still partially intact, and a covered, hidden passage that leads to the Hrazdan river. The Fortress has been connected with neighboring settlements via three underground tunnels dug in the rock. According to Art-A-Tsolum, in 1929, several tombs of the Late Iron Age were unearthed near the Fortress. Since then, all discovered artifacts have been kept in the History Museum of Armenia in Yerevan.

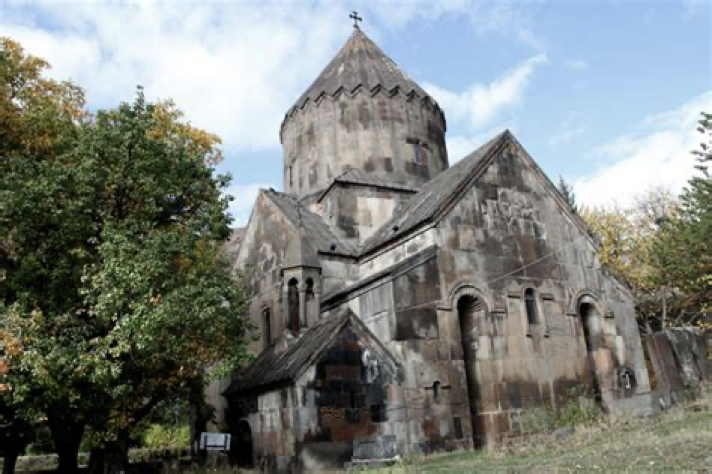

Bjni is home to other churches as well. The largest of the churches is Surp Asdvadzadzin Vank (Holy Mother of God Monastery) built in 1031, which sits within the village just west of the mesa. The following text, furnished by Natalia Ghukasyan, tells us that its main church was built at the same time by Krikor Magistros Pahlavouni by the order of King Hovhannes Smpad and Catholicos Bedros I Gedatarts. The monastery was due to become a residence for high-ranking clergy.

The Church is a domed hall. The fan shaped dome is resting upon a polyhedral drum. The central niche of the Main altar set off with plaster frame is one of the remarkable architectural and decorative elements of this structure. Stone shelves which stretch along the walls were supposedly used for storing a large number of manuscripts written in the Monastery.

St. Asdvadzadzin Monastery is also known as «Magistros’ Lyceum» one of the largest centers of Armenian script, education and science. It enjoyed authority under Catholicos Krikor III Pahlavouni, son of Krikor Magistros (XII).

In 1209 the Monastery was reconstructed by Prince Vahan after Ivaneh. Zakareh Zakarians liberated Bjni from the invading Seljuk Turks (1201 A.D.). In 1211 Father Superior Vrtanes constructed secular buildings on the territory of the Monastery. In 1272 a vaulted chapel was attached to the church from the south.

There are many khachkars and engraved ornaments by prominent Armenian masters on the territory of the Monastery. Two of them are carved by the famous medieval master stone mason Melikset Gazmogh.

The Holy Mother of God Monastery was damaged during Tamerlane’s invasion and the Father Superior of the sanctuary was murdered in the church. According to village lore, besieged Armenian people hid in the catacombs of the Bjni Fortress and beseeched Tamerlane to let them to pray before their inevitable slaughter. Tamerlane granted the people some time which they astutely used to escape through underground tunnels.

In the 15th century St. Asdvadzadzin Monastery once again became one of the largest spiritual and scientific centers of Armenia. There were written a number of manuscripts including the Gospel copied by Father Superior Krikor. According to historical sources (Arakel Davrizhetsi) the Monastery was restored by Armenian Catholicos Philippos I Aghbaketsi’s order under the sponsorship of Bedros from historic Armenian Jugha, Nakhichevan. Philippe I Akhbaketsi’s disciple Father Superior Movses Rabunabed (1646-1666) built a vaulted refectory in the north of the monastery and a pyramidal circular fence.

In the XIX century, rooms for study and monastic cells were built. In 1895 a school building was constructed by order of Armenian Catholicos Mgrdich I Vanetsi (Khrimian Hayrig), the great defender of Armenian national liberation from the Turkish yoke. In 1957 and 1964, St. Asdvadzadzin Church was renovated.

According to legend, the Monastery and Bjni Fortress were connected with secret subterranean roads that led to the Hrazdan River and broad enough so those in the Fortress besieged by marauders could receive food and drink. One section of the subterranean passages was found during the excavations.

Many manuscripts from Bjni dated to the 12th to 17th centuries have survived. The remains of a caravanserai building and bathhouse have been preserved. The Church was reconstructed in 1939, 1949 and 1957. In 1978, excavations revealed a cemetery which has been under examination.

To the south of the monastery a few houses down, there is the small church of St. Kevork (George) built in the 13th century. Some elaborately carved cross-stones (khachkars) are built into the walls of the structure.

On the eastern portion of the village atop a rock outcrop and next to a modern cemetery is the church of St. Sarkis. Built in the 7th century, it is the smallest church in all of Armenia to have a conical dome (gmbet).

Ask us about our walking tours and hiking excursions to the nearby monasteries, churches and chapels in Bjni.

There are three other chapels/shrines in the direct vicinity. Village lore states that Bjni is home to more than 300 chapels. One – Surp Kevork – sits between the Fortress and the village and is constructed of very large stones.

The church of Surp Kevork (Saint George) built in the 13th century sits just a couple houses away from the Holy Mother of God Monastery of Bjni. (Image courtesy of Art-A-Tsolum.)

Dzag Kar is a geological nature monument in Bjni, which is an entirely natural arch formation of stone. The name in Armenian literally means “hole in the rock.”

Dzag Kar is said to have supernatural properties and that s/he who walks through this tunnel will have his/her wishes granted. In the vicinity, there is an intermittently running cold spring called Gatnaghbyur, the waters of which, according to popular belief, increases the milk of lactating women and cures cattle of disease. Dzag Kar is registered among the state monuments of nature by the Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Armenia. One can reach this nature monument from Camp Bjni by hiking the upper tiers of the Bjni mountains or by walking via the main road of Bjni.

Ask us about our walking tours and

hiking excursions to Dzag Kar.

Arishta and Pokhindz: Delicacies of Bjni

Arishta is a traditional homestyle Armenian pasta similar to Italian fettucini. Wheat flour dough is rolled out up to 1.5 mm thick, cut into thin strips with a rolling pin and dried. Then the dried Arishta is browned in a dry frying pan to a pinkish-golden hue. The classic form is served hot with mashed garlic, clarified butter and the gravy of cool, tart Armenian madzun.

Pokhindz is a traditional Armenian flour made from roasted wheat. It is produced by roasting wheat kernels until they turn brown, and then grinding them into flour. This product has been consumed since ancient times, even before the invention of bread. It can be eaten as is or mixed with water and salt to form a porridge-like consistency. Pokhindz is an important element in traditional cuisine on St. Sarkis Day (a movable feast celebrated between January and February of each year).